First published by Newsroom

…the men of New Zealand fought and marched to final and complete victory. Nothing daunted these intrepid fighters; to them nothing was impossible. I am proud to have had the honour of commanding them…

These are the words of the British commander, General Edmund Allenby, describing the involvement of New Zealand forces in the final weeks of battle to overthrow the Turks in 1918.

For many years Anzac commemorations have highlighted the Gallipoli Campaign in the World War I, where New Zealand troops fought alongside those from Australia, Great Britain and Ireland, France, India, and Newfoundland. That campaign saw the loss of over 130,000 men, including 2779 New Zealanders. The battles in France and Belgium have also received considerable attention.

Less well-known is New Zealand’s participation in the Sinai and Palestine campaign. Operations in the final months of the Palestine Campaign, which led to the defeat of the Ottoman forces, were led by New Zealander, Major General Edward Chaytor, whose command – dubbed ‘Chaytor’s Force’ – included the Anzac Mounted Division. What the Allies set out to achieve in Gallipoli was finally realised in northern Palestine and the Jordan Valley – the routing of Turkish forces.

Ironically, the Allied failure in Gallipoli has been enshrined in New Zealand’s war commemorations, while victory over the Ottomans in the Sinai-Palestine campaign has much less presence in our cultural memory.

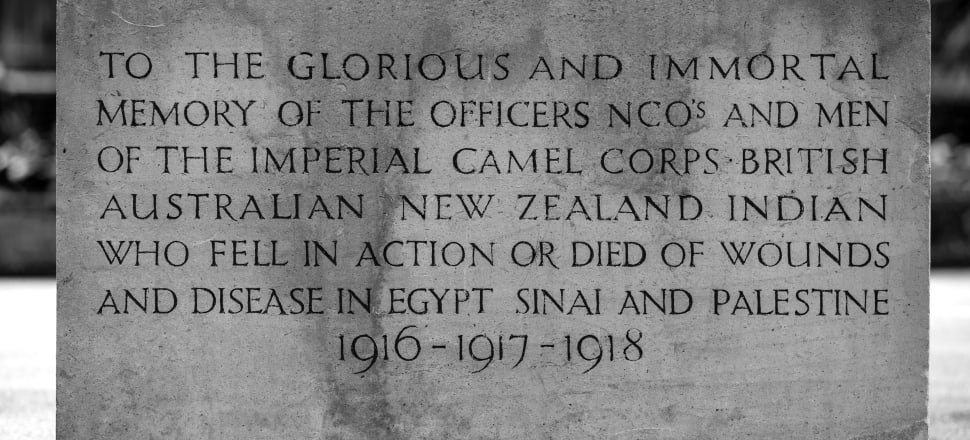

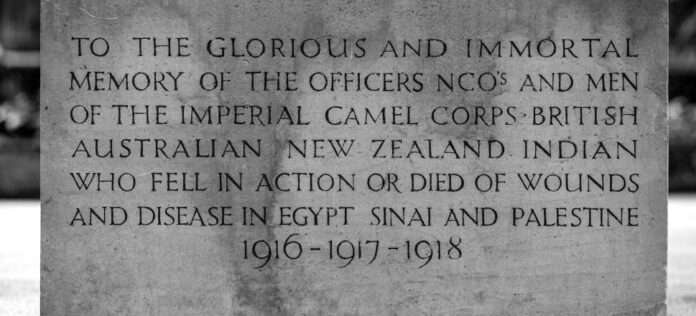

Following the devastating defeat at Gallipoli, the 1800-strong unit of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (NZMR) and the New Zealand companies of the Imperial Camel Corps joined other units from across the British Empire to comprise the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). These forces regrouped in Cairo in December 1915 and prepared to push back the Ottoman forces across the Sinai desert and into Palestine. The EEF took control of the Gaza-Beersheba line, which cleared the way to take Jerusalem. In the final stage of battle, beginning at Megiddo, three Ottoman field armies were destroyed, 76,000 prisoners of war captured and the territories of Palestine, Jordan and Southern Syria conquered.

Part of the reason the efforts of the NZMR were little noticed was that the unit was not accompanied by a war correspondent, as were other units. Contemporary historian, Arthur Briscoe Moore wrote that as a consequence, the work done by New Zealanders was often attributed to others. However, military historian Terry Kinloch argued that, ‘This was perhaps the finest body of New Zealanders ever to serve overseas’. They were a military elite, highly mobile and adept in difficult desert conditions, with a reputation for determination and grit.

What was probably the best known campaign, the battle of Beersheba, was made famous by the Australian movie, The Lighthorsemen. The winning of Beersheba cleared the way to take Jerusalem, a highly symbolic moment which marked the end of Ottoman dominion over the ‘cradle of Christianity’.

Its importance was not lost on General Allenby, who led the campaign. Allenby’s entrance into the Old City was in stark contrast to the ostentatious display made by the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhem II, when he visited Jerusalem in 1898. The Kaiser rode into the city on richly decorated horses and the ancient walls had to be widened for his entry.

Allenby, aware of the gravity of the moment, dismounted his horse and, in an attitude of respect for the holiness of Jerusalem, walked through the city on foot. New Zealanders participated in this historic moment. Fifty dismounted men of the Australian Light Horse and New Zealand Mounted Rifles contributed to the Imperial guard of honour, which stood outside Jaffa gate.

Another battle that proved significant for New Zealand took place near Rishon le Zion on November 14, 1917. The NZMR Brigade captured Ayun Kara in a fierce battle that included close hand-to-hand combat. It resulted in the heaviest New Zealand toll of the campaign with 44 New Zealanders killed and many wounded. This battle was a turning point in the war.

One of the unanticipated outcomes of this engagement was the warm relationship that developed with the Jewish inhabitants of the nearby community of Rishon le Zion, as New Zealand soldiers returned to bivouac in the region over the coming months. It certainly helped that the attractive and well-kept village, described in contemporary sources as a ‘pretty little hamlet’ contained a substantial brick wine-press, with huge cellars where ‘Light white and red wines and cognac could be had at reasonable prices, and were largely in demand’.

The gratitude of the local community was genuine. They undertook to care for the graves of the fallen and erected a memorial column in their honour. A letter was published in the New Zealand Herald at Christmas 1919 by a farmer from the Jewish village of Rishon le Zion, expressing their gratitude:

Permit us, you noblest and brave sons of New Zealand and Australia, to assure you of the sentiments of our hearts and of the esteem and veneration with which we will always hold you. We wish you all well. We wish you a safe and pleasant life.

The friendship between New Zealanders and the local Jewish inhabitants contributed towards a growing support for the Jewish goal of establishing a home in their ancient lands. Many Kiwis identified with the hardworking, ‘hand to the plough’ attitude of the Jewish immigrants and admired their achievements in turning malarial swamps into productive land. The outcome of the military campaign opened the way for the realisation of the Jewish dream of a homeland. The geo-political changes that followed the end of World War I led to the re-drawing of territorial boundaries and the establishment of new global platforms for co-operation.

New Zealand’s Prime Minister William Massey participated in the reconfiguring the new world, in the post-war Paris Peace conferences. These developments helped set the stage for the eventual establishment of a Jewish state. The Palestine Campaign, a battle in which New Zealand was greatly invested, turned out to have great significance for the progress of the war and the future of the Middle East.

Sheree Trotter has recently completed her PhD at the University of Auckland’s Department of History.