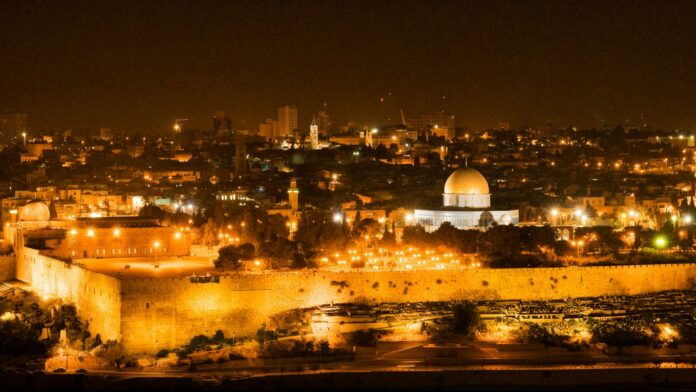

“Ten measures of beauty were bestowed upon the world; nine were taken by Jerusalem, and one by the rest of the world.”1

This quote from the Babylonian Talmud of late antiquity, conveys the magic and mystery of the place that has captured countless imaginations over the centuries.

On the occasion of the 3000 year celebration of Jerusalem, 4 August 1996, Emeritus Professor Dov Bing was invited by the Māori Queen Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu to speak at Turangawaewae Marae about the political, religious and historical meaning of this Holy City. Prof. Bing had met Dame Te Atairangikaahu on several occasions, having accompanied incoming Israeli ambassadors on visits to Turangawaewae Marae to present credentials. The Māori Queen in turn often celebrated Israel’s Independence Day, travelling to Wellington with her husband to attend official events.

Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu’s love for Israel was not unique. Indeed Māori have long had a fascination with the Holy Land. Scattered around the motu are marae and small towns named Hiruharama (transliteration for Jerusalem) – from Hiruharama Hou (Te Tii) marae in the Bay of Islands to Hiruhārama marae (Patiarero) along the Whanganui River near the village of Jerusalem and Hiruhārama marae in the Gisborne district near the village of Hiruhārama.

The Māori prophetic movements of the nineteenth century, such as Pai Marire and Ringatū, drew great inspiration from the plight of the Old Testament Israelites. Te Ua Haumene, leader of Pai Marire saw himself as a new Abraham or Moses and his followers identified themselves as the Chosen People of God, with New Zealand being the new Canaan. Ringatū leader Te Kooti also fully identified the Māori people with the Children of Israel, and the plight of his people with that of the Hebrews.2

The symbolism of biblical narratives and associated motifs has been a source of strength not only to Māori, but to many people, in diverse places and times. Sadly, Jerusalem, the focal point of that strength and inspiration, has now become a political football, kicked around by those who seek to distance the city from its essential Jewish character and history. UNESCO has sought to deny Jewish indigeneity and the degree to which Jewish identity is inextricably linked to Jerusalem. Although this relationship predates the emergence of Islam by centuries, UNESCO resolutions have omitted the name “Temple Mount” for the holiest site in Judaism and only use the Muslim term, “Haram al-Sharif”, creating the absurd situation whereby the “…archaeological digs on and around the site of the Temple Mount, which have unearthed copious evidence of a Jewish connection to the site, may now be designated as destruction of the Muslim site.”

At the 3,000 year Jerusalem celebration that took place in Hamilton in 1996, Dame Te Atairangikaahu, Prof. Bing, Hamilton Mayor Dame Margaret Evans and others planted three olive trees as a symbol of the friendship between Hamilton, Tainui and Israel. Indeed Bing’s long association with Tainui iwi developed over the 46 years spent at the University of Waikato, where he championed Te Timatanga Hou (TTH), a programme equipping those who had been unsuccessful at secondary school to pursue a university education. The TTH programme has produced many high achieving Waikato-Tainui leaders, such as Rukumoana Scaffhausen and Rahui Papa. Bing also gained a lifetime membership award from the Teachers Education Union, for his leading role in establishing equity-oriented programmes at the university – including Māori Studies, Women’s Studies, Labour Studies, and the School of Law.

Prof. Bing’s paper, anchored with reference to classical texts, is a poignant reminder of the special connection of Jews to their ancient city and the importance of historical method in the battle against contemporary assaults on history.

1 Babylon Talmud, Tractate Keddushin 49

2 Elsmore, Bronwyn. Like Them That Dream: The Maori and the Old Testament.

Read the full speech:

Jerusalem

Three Thousand Years of History: The Political, Religious and Historical

Meaning of a Holy City

Professor Dov Bing, Chairperson of Department of Political Science and Public Policy. Address prepared for the Jerusalem 3000 Celebrations in the presence of Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu and His Excellency, Mr Nissan Koren-Krupsky, Ambassador of Israel to New Zealand, Kimi Ora, Turangawaewae, New Zealand, Sunday, 4 August 1996.

- Introduction

To set the tone of this address I have related selected passages from the Bible, the

Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud:

‘Ten measures of beauty were bestowed upon the world; nine were taken by Jerusalem, and one by the rest of the world.

Babylon Talmud, Tractate Keddushin 49

‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yes we wept, when we remembered Zion. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy… –

Psalms 137

…for the law shall go forth from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. And He shall judge among many people, and decide between strong nations far off; and they shall beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.’

Micah 4:2-3

Jerusalem is of course a symbol and a dream. However, besides the heavenly Jerusalem, there are many more Jerusalems. There is the historical Jerusalem. The city of conquerors and kings, prophets, wise men and story-tellers. There is also a sacred, religious Jerusalem, the Jerusalem of faith – the faith of Israel, of Christianity and of Islam.

Jerusalem’s sanctity is unique, not only by reason of its Holy Places and history, but also by reason of the city’s infinite symbolic significance. All of these, identical but divergent, are Jerusalem: terrestial Jerusalem and the Celestial City; Jerusalem of the End of Days and Jerusalem of the World to come; Jerusalem of the Prophets Ezekiel and Zechariah, of the writings of the Dead Sea Sect and of the Revelation of St. John. The selfsame city of twelve pearly gates, the sites of Judgement Day and the Resurrection of the Dead, Jerusalem where the pious made their home. Jerusalem, therefore, is a manifold concept, ingrained in scores of cultures, embodying in itself myriad meanings.

Although Jerusalem evolved into a religious symbol, particularly for Jews and Christians, the Eternal City never lost its importance. ‘And God said, I shall not set foot in heavenly Jerusalem until I have trod in earthly Jerusalem’. Tractate. Yearning for celestial Jerusalem motivated pilgrimage to its earthly counterpart. Some pilgrims to Jerusalem made their way to the Holy City in the face of adversity, others elaborated and restored the Holy Places, and some attempted to achieve dominion over the City as a first measure in the consummation of the prophecies. The Temple Mount with its sanctuaries and the Holy Sepulchre, each in turn, assumed a place in the tradition of sanctity. One of the most striking manifestations of the continuity is the attribution of Jewish folk-tale traditions relating to the Temple Mount, by Christians to the Hill of Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre and restored in turn by Islam to the Temple Mount.

2. The City of David

Let us now turn to the history of Jerusalem. The city had its beginning on the hilltop known as the City of David. Later it expanded northward to embrace also the Temple Mount. The hill on which the City of David was built appears to have been inhabited since the early Canaanite period. The existence of the city in the late Canaanite period is attested to by the Bible as well as by a number of tombs from this era that were uncovered.

The precise circumstances of the capture of Jerusalem by David are shrouded in mystery. The Bible tells the story in two versions, in the First Book of Samuel (5: 4-9) and in the First Book of Chronicles (11: 4-8). At first it was assumed that David captured Jerusalem by means of a ruse. Jerusalem, like Jericho, may have been captured, however, with the aid of a musical instrument. To counter this act of magic, Araunate , the Jebusite ruler of Jerusalem, also ventured into the metaphysical realm. Thus it came to pass that in the year 1005 B.C.E David took the stronghold and named it The City of David.

From the time of King David, when as his capital Jerusalem first entered history as a national entity, the main entrance to the mount on which his son Solomon was to erect the First Temple was from the south. The First Temple was a rectangular building of large squared stones and cedar beams. It consisted of two apartments, separated by a wall in which was a door made of olive wood. The inner room was a perfect cube. It was the most holy part of the sacred edifice, the Holy of Holies, containing the Ark surmounted by two cherubim of olive wood – plated with gold. Throughout the paneling was of cedar, richly adorned with carvings, while the floor was of cyprus wood. The whole complex of buildings, from the Forest House to the Temple, presented an imposing spectacle.

In 587 B.C.E. the Babylonian army laid siege to the city and captured it. Most of the inhabitants were exiled: “And he burnt the house of the Lord, and the King’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem, and every great man’s house burnt he with fire” (II Kings 25:9) This disaster, of which the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel had given ample warning, left Jerusalem desolate for over 50 years.

In 536 B.C.E, after the fall of Babylon, Cyrus, King of Persia allowed those desiring to return to Zion to do so and to rebuild the Temple. In 515 B.C.E. the rebuilding of the Second Temple was competed. But it was not until 445 B.C.E that Nehemiah was appointed governor of Judah. He became responsible for the rebuilding of the city. It was Ezra the scribe who was responsible for the restoration of the authority of the Mosaic Law and for making Jerusalem the undisputed religious center of Judaism.

3. The Hellenistic Period

Jerusalem submitted peacefully with the rest of Judah, to Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E. After the death of Alexander in 323 B.C.E., Prolemy I, King of Egypt captured Jerusalem. Judah had broad autonomy in domestic affairs and Jerusalem continued to be its administrative center.

The Seleucid conquest in 198 B.C.E. was welcomed by the Jews. When in 175 B.C.E. Antiochus IV Epiphanes ascended to the Seleucid throne, the change of Jerusalem into a Hellenistic polis took place. Jerusalem was renamed Antioch. This was a grievous blow to the traditionalists. In 167 B.C.E. Antiochus issued decrees against the Jewish religion that were carried out with special severity in Jerusalem. The Temple was desecrated; its treasures were confiscated. Antiochus converted it into a shrine dedicated to the god Dionysus and ordered the erection of a huge temple of his favourite god, Zeus Olympius.

The revolt against Hellenism which followed was led by Judah Macabee. In December 164 B.C.E. Judah’s forces recaptured Jerusalem and removed the pagan objects from the Temple. Since that time Jews observed the Feast of Dedication, or Hanukkah, in memory of this occasion. Jerusalem became the capital city of the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom, which included the major part of evergrowing economic and religious activity.

4. The Herodian Period

In 63 B.C.E. the Temple wall was breached and the Romans broke into the Temple itself. In 37 B.C.E. the Romans installed King Herod as the new ruler of Judea. He reigned for 33 years until 4 B.C.E. Even though Herod was hated by the people, he initiated a large building programme in Jerusalem. The Temple Mount was surrounded by a wall of huge blocks, of which the Western (Wailing) Wall is but a section. Herod also entirely rebuilt the Temple, doubling its height and richly adorning its exterior. After Herod’s death Judea was made a province of the Roman Empire in 6 C.E. Jerusalem was ruled by Roman procurators who resided in Caesarea. One of the procurators, Pontius Pilate (26-36), under whose rule the execution of Jesus of Nazareth took place, contributed the first acqueduct which brought water to Jerusalem from the vicinity of Hebron. The small Christian community remained in Jerusalem until 66, when it retired to Pella.

The Temple, the Sanhedrin and the great houses of study of the Pharisees turned it into a symbol for Jews everywhere. It was renowned everywhere. The Roman Pliny the Elder wrote that Jerusalem was the most famous among the great cities of the East. A legendary halo surrounded the city. It was also the center of spiritual activity. Houses of learning attracted students from all over the country and from abroad. Its population was estimated at 120,000.

In 66 C.E. the misrule of the procurators finally provoked a revolt against the Romans. The Roman governor of Syria, Cestius Gallus, was defeated. For three years Jerusalem was free. In 70 C.E., the Roman Army, led by Titus, the son and heir of the Emperor Vespasian, attacked Jerusalem. After fierce and bitter fighting, the wall of the Antonia was finally stormed and after a few days the Temple was set aflame on the 9th of Av (August). Most of the people in the city had either been killed or had perished from hunger. The survivors were sold into slavery or executed and the city was destroyed.

Jerusalem remained in ruins for 61 years. The Romans established Aelia Capitolina in 130 C.E. This led to the second Jewish – Roman war. Jerusalem was reoccupied by the Jews, ably led by Bar Kokhba. This state of affairs lasted for almost three years (132 – 135). In 135 Jerusalem was recaptured by the Romans – Aelia became a quiet provincial Roman city.

5. Byzantine Jerusalem

The status of Aelia was completely revolutionised when the Christian Emperor Constantine became master of Palestine in 324. In 326 the Emperor’s mother Helena, visited Jerusalem. As a result of her visit, the Emperor decided to erect the Church of the holy Sepulchre on the spot where according to Christian tradition the True Cross was found.

In 438 the Empress Endoria visited Jerusalem. Due to her intervention, Jews were again allowed to live in the city. After the separation from the Emperor, she settled in Jerusalem (444-460) and built many churches. Byzantine Jerusalem under Justinian was preserved in the Mabada Mosaic Map.

6. The First Moslem Period

The Arabs invaded Erez Israel in 634. They took Jerusalem in 638. It became a provincial town and never regained its previous splendour. The Caliph Omar Ibn Khattab inaugurated a period of 450 years of Moslem rule that ended with the First Crusade at the beginning of the eleventh century. Little is known from primary sources about this period.

Various accounts confirm that Omar had Jews in his retinue who were his advisers. Jewish traditions and beliefs influenced early Islam’s attitude toward the holiness of the Temple Mount. Jews lived in Jerusalem in the early Arab period. A document (in Judeo-Arabic) found in the Cairo ‘Genizah’ reveals that the Jews asked Omar for permission for 200 families to settle in the town. The patriarch opposed it. In the end 70 Jewish families were allowed in.

Omar converted the Temple Mount into a Moslem place of worship. Thus the foundations were laid for the Al Aqsa Mosque. At first it was a large wooden structure, later a new building was constructed, most of which is still extant. Al Aqsa means ‘the distant place’ in Arabic, for this spot was held to be the destination of Mohammed’s Night Journey recorded in the Koran. Built over the remains of the

Second Temple Hulda Gates, the Al Aqsa Mosque’s foundations are consequently insecure and the building has frequently been the victim of natural disasters.

The Dome of the Rock (really a kind of monument, rather than a mosque) was erected on the Temple Mount in 691, during the reign of caliph Abd-al Malik.

In the course of time, there were several changes of dynasty among the Moslem rulers of the city. Thus the periods of rule by the Caliphs of Omayad (660-780) and Abbasid (780-969) dynasties were regarded as flourishing periods. The period of Egyptian Fatimid rule (969-1071), on the other hand, marked a decline; and the subsequent conquests of the Seljuks and the Mongols led to even greater disorder and chaos, until finally Jerusalem was captured in 1099 by the Crusaders.

In the year 1009 the Fatimid Caliph El Haqim, in a fit of religious zeal, ordered all the synagogues and the churches in the city demolished.

Since Islam’s religious association with Jerusalem was limited largely to the Temple Mount, this was the only part of the city that underwent significant changes during the First Moslem period. Gradually, Jerusalem came to be divided into residential zones according to religious affiliation. This division was not imposed on the inhabitants of the city, but came about of itself. Christians, Moslems and Armenians occupied roughly the same quarters they occupy today. The Jews lived in the quarter near the Dung gate; towards the end of the period the northern position of the Moslem Quarter came also to be called the Jewish Quarter.

7. The Crusaders (1099-1187)

The Crusaders ruled Jerusalem during most of the 12th century. They did in fact again hold part of the city from 1229 to 1244. The troops of Flanders and northern France, led by Godfrey de Bouillon, scaled the walls in the north-eastern sector, which was defended by both Muslims and Jews. A Provincial force, led by Raymond of St. Gilles, surmounted the wall adjoining Mount Zion, while the Normans from Sicily entered the northwest. The population, Muslims and Jews alike, was massacred. Jerusalem, became the capital of the crusaders’ kingdom. Christian Arabs from Transjordan and Syria were settled in the former Jewish quarter.

The various quarters in the city were also organised along ethnic lines. In the present-day Jewish quarter were Germans, in the Armenian quarter of today were the French. There were also Hungarian, Spanish and English communities. The Dome of the Rock was renamed “Templum Domini’ – Temple of the Lord, and the Al Aqsa Mosque was called ‘Templum Salomonies’ – Temple of Solomon.

The crusaders’ rule invigorated Christian religious life. Many Christian traditions associated with Jerusalem were established. Thus the tradition of Via Dolorosa was defined. Many Muslim shrines were turned into churches.

Crusader Jerusalem fell to Saladin in 1187. Only in 1229, under the Emperor Frederick II did Christian rule return to Jerusalem and then only for a brief period of fifteen years.

8. The Mamelukes (1187-1517)

After Jerusalem had fallen to Saladin in 1187, the city passed through many hands till its conquest by the Turks in 1517. The Mongols invaded Jerusalem in 1260. At the end of that year the Mamelukes defeated the Mongols at En-Harod.

The Mamelukes did not care to fortify Jerusalem and repopulate it. Under their long rule Jerusalem became a town of theologians. It was administered by a low-ranking Mameluke appointed by the deputy of the Sultan of Damascus. During this period Jerusalem remained a very poor town. At the end of the 15th century Jerusalem probably had no more than 10,000 inhabitants. The Dominican Felix Fabri, who was in Jerusalem in 1483, says that there were 1,000 Christians, and the Jewish community number 100-150 families. The total population was no more than 10,000.

The Mameluke rulers generously endowed religious establishments, such as mosques and colleges. Since the number of the madrasas had increased, Jerusalem became a center of Islamic studies in the later Middle ages. Fanaticism and persecution of non-Muslims were frequent.

The role of the Jews in Jerusalem was modest. At the beginning of the 15th century immigration of Jews from Europe began. In the beginning of the 16th century there were a number of Jewish scholars in Jerusalem.

9. The Ottomans (1517-1917)

In December 1517 the Turkish Sultan Selim I conquered Jerusalem. Under his successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, the city was vastly improved and took on an aspect of splendour. The present-day wall around the Old City of Jerusalem was his work. The construction of the wall lasted from 1537 to 1541. Suleiman also introduced changes in the buildings on the Temple Mount. Two Jewish sources also indicate that he improved Jerusalem’s water supply, especially for the Temple Mount area. The conduits bringing from the vicinity of Solomon’s Pools were repaired and widened.

After the reign of Suleiman, Jerusalem entered a period of considerable decline. The governor of the district (sanjak) was usually of lower status than the other local regional rulers (Safed, Nablus, Gaza) since the central authorities regarded Jerusalem as no more than a town bordering on the land of Bedouin.

During their 400 year reign only a few Turks settled in the country. Arabic remained the spoken language. According to the Ottoman records of land registration from the 16th century, the inhabitants of the district of Jerusalem were much fewer in number than those of Gaza, Nablus and Safed. Accordingly, the income of Jerusalem’s governor was smaller than that of other governors.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Jewish Jerusalem attracted kabbalists who were awaiting the imminent redemption. The communities of Egypt and Syria aided the Jerusalem community. According to official censuses in the 1530’s the number of Jews in Jerusalem ranged between 1,000 and 1,500. In the 17th century immigrants from Turkey, North Africa and Italy settled in Jerusalem. The city also supplanted Safed as the centre for the study of Kabbalah. A quarter of the Jewish population were scholars and rabbis. The remainder craftsmen and small businessmen.

In the pilgrim literature Jerusalem is described as a ghost-town, underpopulated and with much of its area turned into deserted fields. Well into the 19th century, Jerusalem continued to present a dreary, cheerless aspect.

Perhaps more than anything else, the opening of foreign consulates in Jerusalem paved the way to the city’s development. Under a system of granting concessions (‘capitulations’) to foreign powers, foreign companies were able to invest in the

Ottoman Empire, including Jerusalem. With the consulates extending their protection and services to Jews as well, there was a rapid growth in the Jewish population. At the start of the 19th century, the Jews contributed but one-fourth of the city’s population; by mid-century they were almost one-half, growing rapidly, in the years that followed, to 60-70% of the total. All these changes were also reflected in the appearance of the city. The streets were paved with stone (1864-5) and gas lighting installed (1868). In many of the streets water and sewage pipes were laid.

With the rapid growth of the Jewish population, Jews began to establish residential neighbourhoods outside the Old City walls. Several Christian neighbourhoods followed as well as Moslem ones.

10. The British Mandate (1917-1948)

When the British took the city in December 1917 there were more than 30,000 Jews in Jerusalem out of a total population of 60,000. The military administration that operated in the area was replaced in 1922 by a civilian administration, under the terms of the Mandate bestowed upon Britain by the League of Nations. Jerusalem became the centre of British government in Palestine. The Municipal Council was composed of six Jews and six Arabs (four Moslems and two Christians).

The British era saw the establishment of institutions in both the Jewish and Arab sectors. The Hebrew University was finally opened by Lord Balfour in 1925. The 1931 census showed 51,222 Jews; 19,894 Muslims and 19,335 Christians.

In April 1920, the first Arab riots took place; major recurrences broke out in August 1929 and in the Arab insurrection of 1936-1939. In Jerusalem, hostility was particularly rife, the city represented a religious and political focus for both people. At the close of the British Mandatory Period, the population of Jerusalem numbered 165,000 of whom 100,000 were Jews, 40,000 Moslems and 25,000 Christians.

11. Jerusalem Divided (1948-1967)

On 29 November 1947 the UN resolved to partition Palestine and internationalise Jerusalem. The resolution was accepted by the Jews, but rejected by the Arabs.

Fighting broke out the following day. Siege, destruction and hunger were once more Jerusalem’s lot. The Transjordanian Arab Legion invaded the Old City of Jerusalem.

Before the fighting stopped almost a year later, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City was destroyed and its people driven out by the Jordanian Army. Mt. Scopus, a vital medical and educational focus, became an isolated enclave severed from the city. Its hospital and university remained closed until 1967. A total cease-fire came into force on 3 April 1949.

In December 1949 Jerusalem for the third time in history became once again the capital of Israel. The city began to be rehabilitated and rebuilt. Suburbs were built to house refugees from quarters of Jerusalem which remained in Arab hands, new immigrants, survivors of the Nazi holocaust and Jewish refugees from Arab countries.

At the close of the 1948 war, there remained 65,000 people in the Jordanian section of Jerusalem, more than half of them living within the Old City. Stagnation set in, and by 1967 these were still less than 66,000 people, about 25,000 in the Old City. The Christian community had shrunk to about 10,800.

12. Jerusalem Reunited (since 1967)

Jerusalem was reunited in 1967 in the wake of the Six-Day War. Shortly after the war, all the walls, barriers and obstacles were removed and Jerusalem became one again: Jews returned to the Jewish Quarter and were once again able to visit the Western Wall and the Temple Mount. Moslems and Christians were assured free access to their sacred sites.

Before its unification, the population numbered 198,000 on the Israeli side and 66,000 on the Jordanian – a total of 264,000. By 1994 the total population of Jerusalem had more than doubled to 567,200. Of these 406,400 were Jews; 145,800 Muslims and 15,000 Christians. Thus Jerusalem has became the largest municipal unit in Israel. Today Jerusalem is a prosperous city. Its many secular and religious educational institutions have made it into the intellectual centre of the Jewish world.

It is also the city where, Jew, Moslem and Christian meet to discuss what they have in common and on which questions they differ. The city’s cultural heritage is being unearthed and preserved with meticulous care, irrespective of its origin and religious life is pursued by all within its walls in complete freedom.

13. Jerusalem: The Islamic Tradition

The sanctity of Jerusalem in Islam is an act. Though not mentioned in the Koran,

Jerusalem is al-Kuds (the Holy One), or al-Kuds al-sharifa (the Noble Holy One). In this manner it was referred to by medieval Arab travellers and writers.

The Prophet Muhammed never visited Jerusalem. His message was profoundly influenced by Christian and Jewish influences. The holiness of Jerusalem was part of that legacy and indeed the original direction of prayer (qibla) was not to Mecca but to Jerusalem.

The Koran, Sura 17:1 states: ‘Praise be to Allah who brought his servant at night from the Holy Mosque to the Remote Mosque, the precincts of which we have blessed.’ According to early Islamic tradition, the Prophet Muhammed was miraculously transported from Mecca to Jerusalem and it was from there that he made his assent to heaven. By this interpretation, Islam linked itself to the traditional holiness of Jerusalem in Christianity and Judaism and integrated this legacy with its own religious system.

14. Jerusalem: The Christian Tradition

The Christian attitude to the Holy Land and to the Holy City is far more complex.

The true home of the Christian – according to the medieval conception – is the heavenly Jerusalem. The true terrestrial Jerusalem which united with the one in heaven is wherever the perfect Christian life is lived.

For the Christians it is not the Temple and its Holy of Holies that is the center, but Christ. It is not the Holy City or Land that constitute the area of holiness, but the new community, the body of Christ.

The beginnings of the first Christian community, Christ’s childhood and manhood, his ministry and preaching, resurrection and accession – all these took place on definite spots in this particular city and land. Therefore, Christians have always cherished Palestine as a “holy land’, and Jerusalem as a ‘holy city.’

15. Jerusalem: The Jewish Tradition

The Jewish tradition is very different. Jerusalem entered Israelite history and religious consciousness under King David. Under David, Jerusalem became the symbol and the most significant expression of the transition from ‘peoplehood to the formation of a ‘nation’ and ‘state’. However, when the state ceased to exist, Jerusalem did not lose its importance and symbolic value that had been conferred on her by David. The meaning of Jerusalem for the Jewish people is spelled out in the Prophets and in the Book of Psalms. Jerusalem and Zion are synonymous, and they came to mean not only the city but the land as a whole and the Jewish people as a whole.

For three thousand years Jews have considered the earthly Jerusalem/Zion as the centre, materially and spiritually, of their existence. For almost two thousand years they turned towards Jerusalem/Zion in prayer, no matter in which part of the globe they found themselves. There seems to be a crucial difference between the Jewish relationship to Jerusalem on the one hand, and that of Christianity and Islam on the other. The difference has been well expressed by Professor Krister Stendahl, formerly Dean of the Harvard Divinity School and subsequently Bishop of Stockholm, when he wrote:

‘For Christians and Muslems that term (holy sites) is an adequate expression of what matters. Here are sacred places, hallowed by the most holy events, here are the places for pilgrimage, the very focus of highest devotion….But Judaism is different. The sites sacred to Judaism have no shrines. Its religion is not tied to ‘sites’ but to the Land, not to what happened in Jerusalem but to Jerusalem itself.’

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 87225 more Infos: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 73760 additional Info to that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: israelinstitute.nz/2021/03/prof-dov-bing-jerusalem-three-thousand-years-of-history/ […]

Comments are closed.